Football in Australia isn’t being held back by passion, participation, or community support.

It’s being held back by local government failure.

From a CEO perspective, the warning signs are no longer subtle — they’re screaming. Confidence towards councils is collapsing, clubs are done believing the rhetoric, and the people carrying the game every weekend are telling us the same thing: councils don’t understand football, don’t consult properly, and don’t plan for growth.

This isn’t opinion anymore.

It’s measurable.

And it should embarrass every policymaker in the country.

Football in Australia isn’t struggling because of a lack of passion. It isn’t struggling because communities don’t care. And it certainly isn’t struggling because participation is declining.

Football is struggling because, at the local government level, confidence is collapsing. What is more, the people closest to the game can feel it.

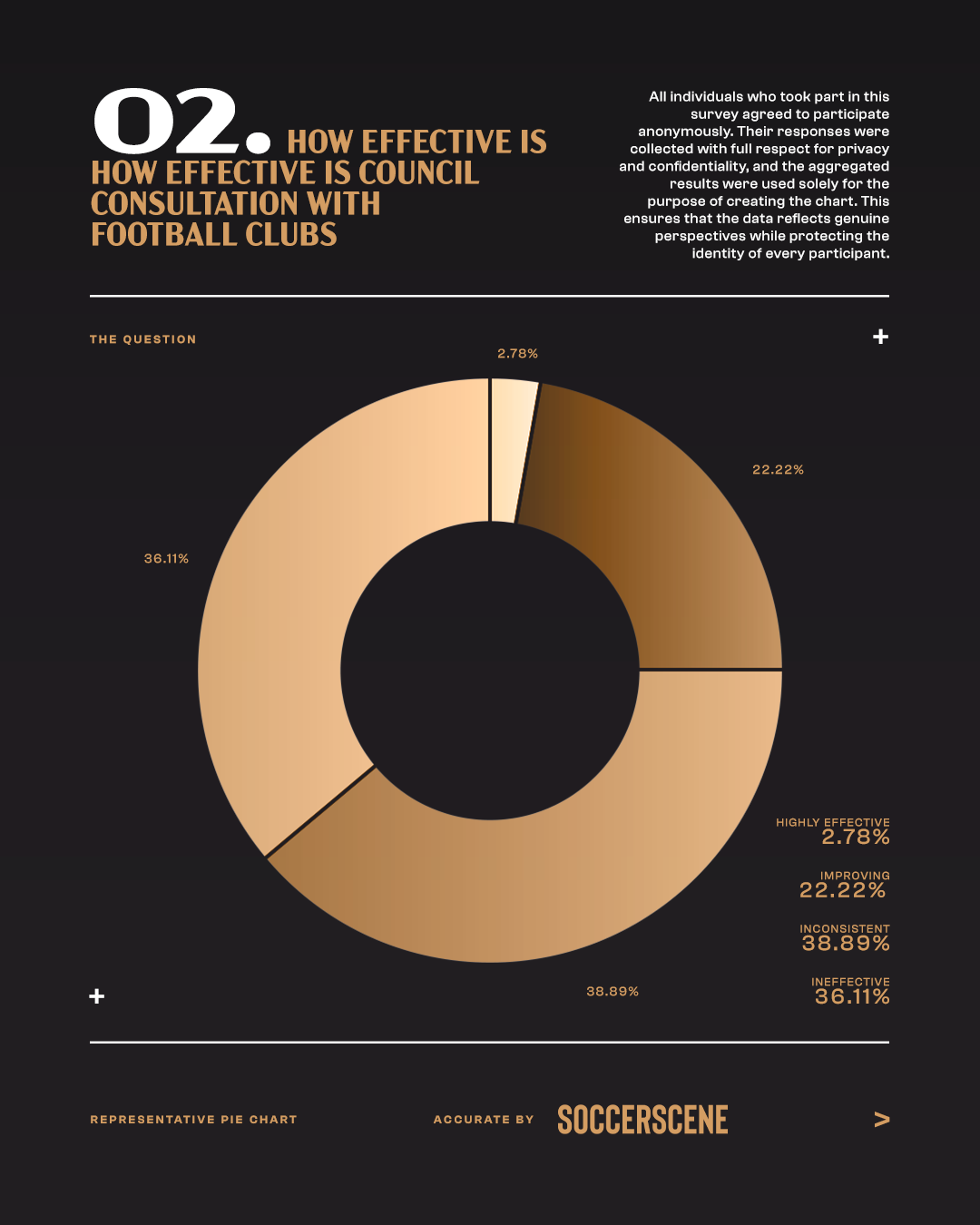

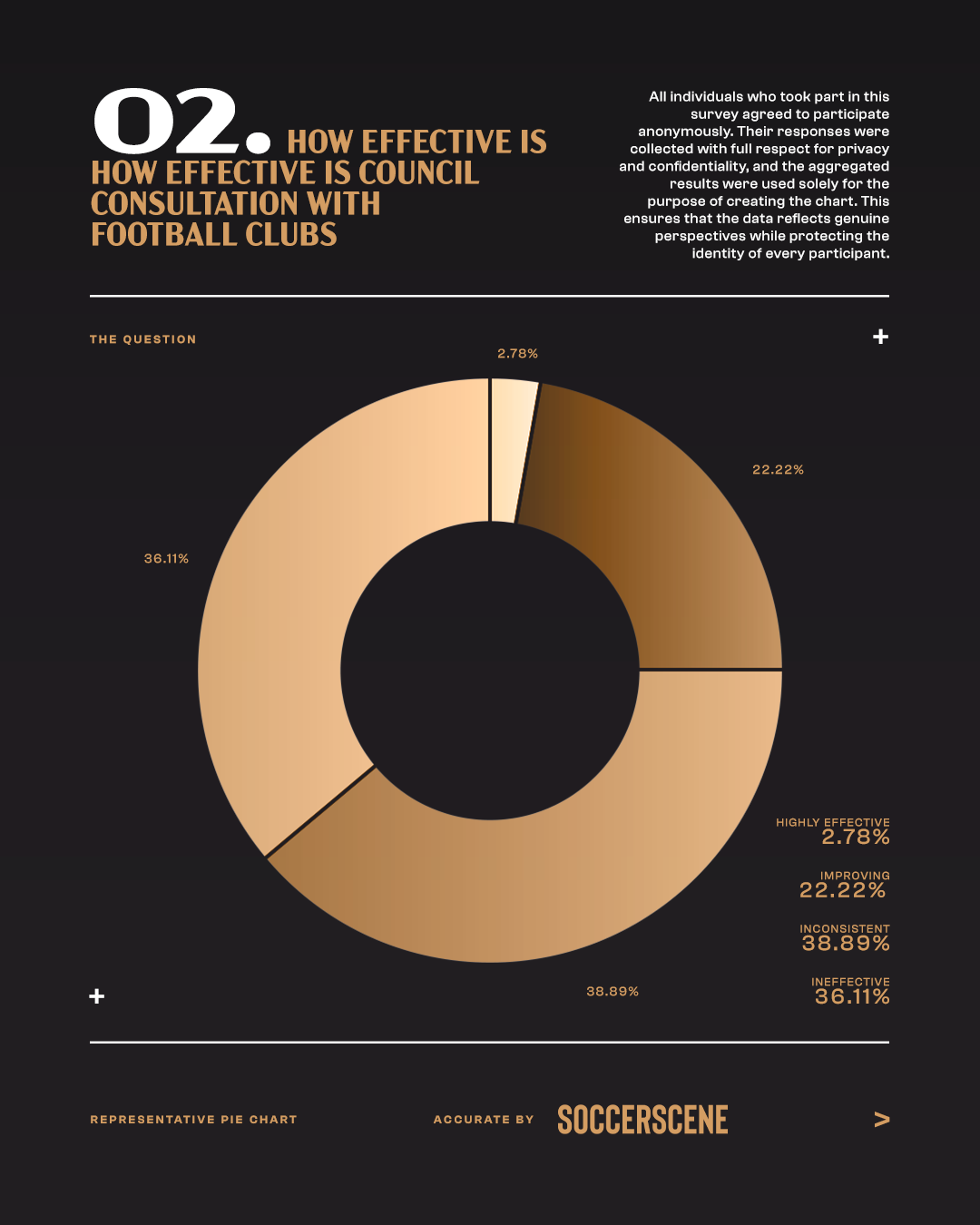

Soccerscene’s latest survey on council readiness and football planning shows something deeply confronting: trust in councils is at its lowest point, and clubs no longer believe the rhetoric. Councils frequently speak about “supporting the world game” and “investing in community sport,” but the data tells a different story.

The people building the game every weekend, people such as presidents, coaches, volunteers and administrators, are telling us councils do not understand football demand, do not consult effectively, and do not plan for long-term growth. And that’s not an emotional opinion. It’s now measurable.

In our survey, over 61% of respondents said their council has limited or no understanding of football participation demand. Consultation outcomes were even worse: 74% said council consultation is inconsistent or ineffective. And when asked if facilities are being planned with long-term growth in mind, the answer should stop every policymaker in their tracks: more than 71% said planning is short-term or non-existent.

Results graphic from Soccerscene’s January industry survey:

This is not a small problem. This is a national warning sign.

Football is not a niche sport. It’s the world’s sport

Councils across Australia are making decisions as if football is still an emerging code, competing for scraps. That thinking is decades out of date.

Football is not only Australia’s largest participation sport in many communities – it is also part of the global economy of sport, the largest sport market on earth, and a cultural engine that connects Australia to Asia, Europe, Africa and the Americas.

When councils underinvest in football infrastructure, they’re not just failing local clubs. They’re failing an entire economic pipeline: participation growth, player development, coaching pathways, community engagement, multicultural integration, women’s sport, health outcomes, events, tourism, and commercial opportunity.

And yet, football is still treated as the code that should “make do”.

The Glenferrie Oval case: a perfect example of the imbalance.

Take the redevelopment of Glenferrie Oval and the historic Michael Tuck Stand in Hawthorn.

This is a major project with a total estimated investment of approximately $30 million, with the City of Boroondara allocating $29.47 million over four years to transform the site into a premier hub for women’s and junior AFL.

Let’s be clear: there is nothing wrong with investing in women’s sport. In fact, it’s essential.

But this investment is also a symbol of something football people have been saying quietly for years: councils understand AFL. Councils prioritise AFL. Councils know how to justify AFL.

They don’t do the same for football, despite its participation scale, multicultural reach, and global relevance.

Across the country, football clubs are being told there is “no funding,” that “planning takes time,” or that facilities “can’t be upgraded yet.” Meanwhile, we see multi-million-dollar grandstands, boutique ovals, and legacy infrastructure funded and delivered for other codes.

Football isn’t asking for special treatment.

Football is asking for fair treatment based on reality.

Councils are stuck in a domestic mindset – while football is global.

Here is the core issue: local councils are making decisions through a domestic sporting lens, while football operates in a global one.

Football isn’t just a Saturday sport. It’s a worldwide industry with elite pathways, commercial frameworks, international investment, and an ecosystem that Australia must compete within.

If councils don’t understand this, they will keep making decisions that shrink our competitiveness.

And this is where the stakes become real.

Australia is not only competing against itself. We are competing against countries like Japan and South Korea, who treat football as a national asset. They don’t leave football infrastructure to fragmented local decision-making without a clear national framework. They invest strategically, align education with delivery, and build systems that create long-term advantage.

We cannot keep pretending we are in the same conversation globally while our local facilities remain stuck in the past.

Clubs are carrying the burden – and it’s breaking the system.

The survey results point to a harsh reality: football clubs feel like they are carrying the weight of growth alone.

When asked what the biggest council-related challenge is, nearly 49% said funding is not prioritised, while others pointed to poor facility design, limited engagement, and slow planning processes.

This isn’t just an inconvenience.

It is creating volunteer burnout, club debt, stagnation in women’s participation, and barriers to junior growth. It is forcing clubs into survival mode – patching up grounds, sharing overcrowded facilities, and trying to grow in spaces that were never designed for modern football demand.

And when planning is short-term, the problem compounds. Councils aren’t just falling behind- they’re building the wrong solutions.

So what do we do? We stop reacting and start leading.

Football cannot keep waiting for councils to “get it” organically. That approach has failed.

What we need now is a national strategic response that is structured, intelligent, and relentless.

This is where football must learn from high-performing football nations not just on the pitch, but in governance, philosophy, and decision-making.

A powerful example is Korea’s “Made in Korea” project, which was built to identify structural gaps, align stakeholders, and create a unified development philosophy. It wasn’t just a technical framework, it was a national alignment strategy.

Australia needs the off-field equivalent.

A National Football Facilities & Readiness Taskforce.

I believe the time has come to establish a National Football Facilities & Readiness Taskforce, made up of the most capable minds across the game and beyond it.

Not another committee. Not another meeting group.

A taskforce.

It should include leaders from football, infrastructure, urban planning, commercial strategy, government relations, and corporate Australia. We should be selecting the most intelligent and effective people in the country, not based on titles, but based on outcomes.

This taskforce should have one clear mission:

Educate, influence, and reshape how councils plan, consult, and invest in football infrastructure.

Alongside a taskforce, we need long-term strategic working groups embedded across the states, designed to:

educate councils on football participation demand and growth forecasting

standardise best-practice facility design and future-proofing

create consistent consultation frameworks

align football investment with economic, health and multicultural outcomes

build a national narrative that football is an asset rather than a cost

Because right now, the survey shows councils aren’t prioritising football for economic reasons. In fact, only 2.56% of respondents said councils should prioritise football due to economic benefits. This is not because it isn’t true, but because councils haven’t been educated to see football that way.

That is a failure of strategy, not a failure of the game.

This is bigger than facilities – it’s about Australia’s place in the world game.

If we want to be taken seriously as a football nation, we must build a country that treats football seriously.

Not just at elite level.

At local level – where the entire pyramid begins.

The message from the survey is blunt: football’s confidence in councils is collapsing. But within that truth is also an opportunity.

Because when trust hits its lowest point, change becomes possible.

The next step is ours.

We either continue accepting a system that doesn’t understand the world game – or we build one that does.